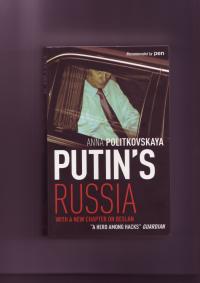

The book from which the excerpt in the previous post is taken – Putin’s Russia, by Anna Politkovskaya (translated by Arch Tait, Harvill, 2004 - 302pp.) – strikes me as a remarkable achievement. Its author, who knew the reality of the Soviet Union at first hand, and watched the country’s shabby decline during the 1970s and 80s, has provided a clear and comprehensible analysis of what happened in the aftermath of that decline: the engineering of a society in which the very principles of society itself were subjected to a merciless attack, not from outside, but from the very organs of government themselves, and from the leaders who were supposed to be in charge. A disastrous and racist “war” in Chechnya, which was really not much more than a large-scale pogrom directed against a small and vulnerable people with the use of modern military technology and brute force, served as the basis for this project of undermining and subverting any possibility of creating a stable or unified society in Russia itself. This process of disintegration, begun by Yeltsin, was reinforced and taken further by Vladimir Putin, a KGB operative whose cynical disregard for the people who are nominally under his control is evidenced by his indifference to their suffering, and his crushing of dissent. In her book, Politkovskaya focuses on a number of case studies: the case of the war criminal Colonel Yury Budanov, who raped and murdered Elza Kungayeva, a 15 year old Chechen girl; the fates of young people whose lives were ruined by the ham-fisted and, it seems, deliberately bungled transition from Communism to the “free market” economy; the rise of a fascistic materialism, evidenced in the career of one of the author’s former female friends; the corruption that permeates the whole of society; the workings of the Russian mafia, which rose from the crime-steeped ashes of Communism; the ill-paid and members of the armed forces, the bullied and tortured conscripts, the malnourished naval commander in charge of a fleet of nuclear submarines whose warheads are in a dangerous state of decay; the innocent people who were gassed and shot by Russian government forces during the “freeing” of the hostages in the Nord-Ost crisis; the black tragedy of Beslan. From these studies, Politkovskaya creates a sensitively-written portrayal of a society not only in collapse within itself, but also in a condition that could without much prompting spill over and threaten the rest of Europe and beyond. Her concluding paragraphs are a despairing appeal for help from the outside world before it is too late:

We cannot just sit back and watch a political winter close in on Russia for another several decades. We want to go on living in freedom. We so much want our children to be free and our grandchildren to be born free. This is why we long so much for a thaw in the immediate future, but we alone can change Russia's political climate. To wait for another thaw to come our way from the Kremlin, as happened under Gorbachev, is now foolish and unrealistic, and neither is the West going to help. It barely reacts to Putin's "anti-terrorist" policies, and finds much about today's Russia entirely to its taste: the vodka, the caviar, the gas, the oil, the dancing bears, the practitioners of a particular profession. The exotic Russian market is performing as the West has come to expect, and Europe and the rest of the globe are perfectly satisfied with the way things are going on our sixth of the world's land mass.

All we hear from the outside world is "Al-Qaeda, al-Qaeda", a wretched mantra for shuffling off responsibility for all the bloody tragedies yet to come, a primitive chant with which to lull a society which wants nothing more than to be lulled back to sleep.

No comments:

Post a Comment